The recent announcement by former United States President Donald Trump imposing a sweeping 14 per cent tariff on Nigerian exports has sparked deep concern among economists, trade analysts, and business leaders in Nigeria. The new policy, which took immediate effect, threatens to disrupt an estimated $10 billion in annual exports to the US, placing key sectors such as crude oil and agriculture in jeopardy.

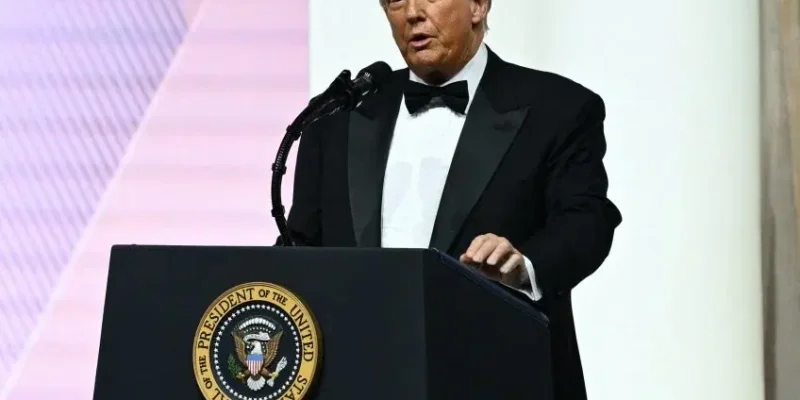

Announced during a “Make America Wealthy Again” event in the White House Rose Garden, Trump’s tariff regime marks a significant departure from the decades-long free-trade principles that have underpinned global commerce since the Second World War. The 14 per cent tariff on Nigerian goods is part of a broader strategy targeting over 50 countries, including China, India, the UK, and several African nations, with tariffs as high as 50 per cent.

Although Trump claimed the policy aims to “rebalance global trade” and protect American industries, Nigerian stakeholders warn that the consequences could be severe, particularly for a country like Nigeria, which relies heavily on oil exports for foreign revenue.

Sheriff Balogun, National President of the Nigerian-American Chamber of Commerce (NACC), said the policy threatens the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), a two-decade-old trade deal that has seen Nigeria export approximately $277 billion worth of goods—primarily crude oil—to the US since its inception in 2000.

“Nigeria’s exports to the United States currently range between $10bn and $12bn annually. The vast majority of this comes from crude oil. This new tariff risks destabilising that balance and weakening our foreign earnings,” Balogun stated.

Under AGOA, Nigeria enjoyed duty-free access to the US market for certain goods, a benefit now potentially undermined by the new reciprocal trade measures. Analysts believe Nigeria’s non-oil exports—such as cocoa, rubber, and certain agricultural products—could bear the brunt of the new tariffs.

Although some energy products like crude oil are currently exempt from the tariff, experts argue that the policy’s indirect effects could still impact Nigeria’s economy. Johnson Chukwu, CEO of Cowry Asset Management, noted that while crude oil itself may not be directly affected, reduced global industrial production triggered by the tariffs could lower demand, dragging oil prices down.

“Once global production slows, demand for crude oil will fall, resulting in lower oil prices. That will hurt Nigeria’s revenue projections,” Chukwu explained.

Already, the international oil market is reacting nervously. Brent crude fell below $70 per barrel on Thursday after OPEC+ unexpectedly increased oil production, compounding Nigeria’s challenges.

Higher tariffs on imported goods like wheat and vehicles, as well as disruptions in global supply chains, could also fuel inflation in Nigeria. The country relies heavily on US imports for cars, refined petroleum, and food items like wheat.

Afreximbank’s research suggests the tariffs could reduce Nigeria’s export revenues, disrupt foreign investment, and drive up production costs for local businesses. The cumulative effect, experts warn, may be slower economic growth, increased hardship, and a weaker naira.

Framing the tariffs as the dawn of a new era of “fair trade,” Trump argued that nations like Nigeria have imposed unfair tariffs and trade barriers on US goods for too long. The Trump administration cited Nigeria’s 27 per cent tariff on US exports as justification, claiming it created a trade imbalance detrimental to American businesses.

“This is one of the most important days in American history,” Trump said during his speech. “We are going to supercharge our domestic industrial base and force open foreign markets that have shut out American products for years.”

Yet critics, including the European Union and trade economists, warn the move could trigger a global trade war, destabilise the international economy, and hurt developing nations the most.

According to data from the National Bureau of Statistics, Nigeria’s trade with the US over the last decade amounted to N31.1 trillion (approximately $70 billion), with a modest trade surplus of N1.64 trillion. While exports to the US have grown in recent years—reaching a record N5.52 trillion in 2024—experts fear these gains could be reversed by the new trade measures.

Nigeria is not alone. Other African countries have been slapped with steep tariffs as part of the US’ recalibrated trade stance. These include Mauritius (40%), Lesotho (50%), Algeria (30%), Namibia (21%), Ghana and Kenya (10% each), and South Africa (30%).

On a broader scale, the US introduced a baseline 10 per cent tariff on all imports, targeting over 50 countries. Some of the steepest include Vietnam (46%), Cambodia (49%), Taiwan (32%), and Switzerland (31%).

Muda Yusuf, CEO of the Centre for Promotion of Private Enterprises, described the new US policy as the “practical closure” of AGOA. He warned that global inflation, higher interest rates, and reduced investment in developing markets could follow.

“If US inflation worsens, the Federal Reserve may raise interest rates again, causing capital flight from emerging economies like Nigeria. That will put more pressure on our already volatile naira,” Yusuf said.

However, he also pointed out that the shifting global trade landscape could present opportunities. As countries seek alternative trading partners, Nigeria could position itself strategically—if it invests in local production and value addition.

Sola Obadimu, Director General of the Nigerian Association of Chambers of Commerce, Industry, Mines and Agriculture (NACCIMA), described Trump’s policy as consistent with his “America First” agenda and urged Nigeria to draw lessons from it.

“Every country, including the US, creates policies that favour its own economy. We should do the same. We cannot continue exporting raw materials and importing finished products. It’s time to industrialise,” Obadimu said.

He stressed the need for long-term investments in infrastructure, especially electricity. “We cannot industrialise on generators. We need at least 150,000 megawatts of stable power to add value to our raw materials and create jobs,” he added.

While the future of the tariffs remains uncertain—especially with the possibility of a new US administration rolling back Trump’s measures—experts agree that Nigeria must not wait passively.

The consensus is clear: Nigeria must reduce its overreliance on crude oil exports, develop robust manufacturing capabilities, and invest in competitive industries that can thrive with or without preferential trade agreements.

The coming months will be critical for Nigeria as it navigates this complex new global trade reality—one that may require tough decisions, bold reforms, and a renewed focus on self-reliance and economic diversification.

Comments